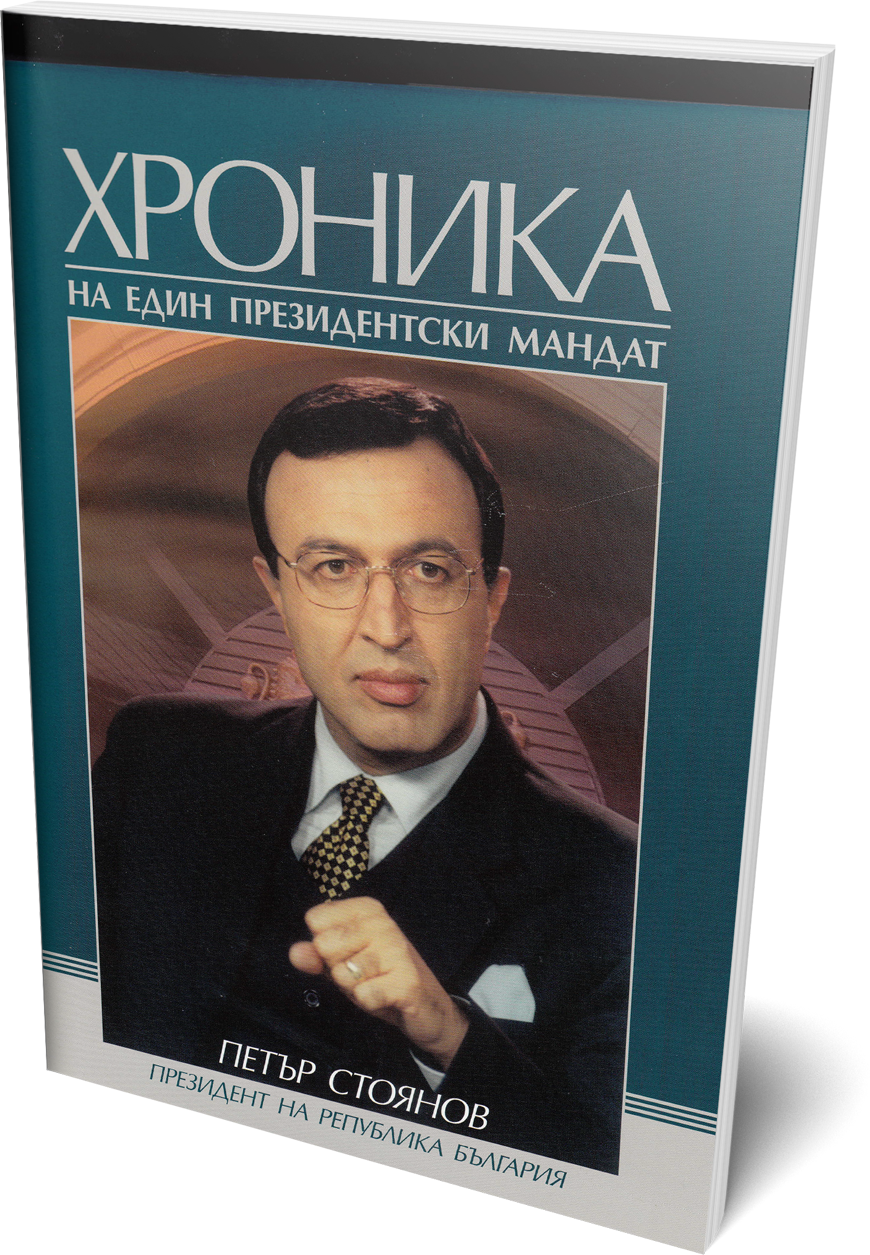

Petar Stoyanov

24 November 2002

The Washington Post

NATO’s 19 members gathered in Prague last week and invited seven countries of Central and Eastern Europe to join the alliance. With that, the long debate in both Western and Eastern capitals about the advantages and shortcomings of an expanded alliance come to an end. For me, as Bulgaria’s former president, these membership invitations carry substantial moral weight, because of the dark history of the past and the bright promise of the future.

As serious as this discussion is, however, it can hardly reflect the feelings, personal suffering and dashed hopes of an entire generation of Eastern Europeans whose lives today are at their sunset. In their youth, after World War II, those people, like millions across the globe, eagerly planned their peaceful future. But their plans never came true — the iron fist of communism crushed their dreams for a free and meaningful existence.

Many years ago, when I was a boy and Bulgaria was still in the shadow of the Soviet empire, I asked my father, who had spent time in a concentration camp for his anti-communist convictions, why he hadn’t left the country before the process of Sovietization started. Had he not realized that the Bolshevik system wouldn’t tolerate unconventional thinking? Had he and his peers not been able to foresee that Bulgaria might find itself in the Soviet orbit and that the Stalinist gulag model could be established in his country?

“We didn’t expect that the West would betray us,” my father replied flatly.

I have been thinking over these bitter words for many years. Despite the disastrous division of Europe in Yalta after the war, my father and his friends never changed their attitude toward the West. For them, it continued to represent the free human spirit and free enterprise. While it certainly had its imperfections, the alternative was a world built upon a fat lie and constant humiliation, which the communist rulers quite accurately called the “socialist camp.”

At that time such thoughts could, of course, be voiced only in the small apartments where former members of the Bulgarian political, cultural and business elite met. They were all branded “enemies of the people” because their beliefs could not be reconciled with the “values” of the communist regime.

Those men and women had no chance of accomplishing anything significant in their professional lives, and most of them were even deprived of practicing their professions. The rigid censorship denied them the opportunity to publish anything in the press. They did not have the right to travel beyond the Iron Curtain, although they had superb knowledge of European culture and tradition.

Yet they never gave up hope, aware that the United States and Western Europe had already joined efforts in building a common system of security and safeguarding demo cratic values.

I was in high school when, in 1968, the people of Czechoslovakia stood up against Soviet tanks in defense of their human dignity. I was glued to the radio listening to the latest broadcasts of Radio Free Europe and the Voice of America. Gathered in our kitchen, my father’s friends kept their fingers crossed for the Czechs and Slovaks and fretted: “Why is the West not coming to their rescue? Why isn’t NATO doing anything?”

Today these questions sound naive. Unlike in the movies, in politics the good guys don’t always turn up on time to defeat the bad guys. And how was it possible for the dissidents in Eastern Europe to understand the concept of realpolitik — the notions of strategic interests and balance of power — sitting in their kitchens in Sofia, Bucharest and Budapest?

Years later, after the lifting of the Iron Curtain, when I had myself become a politician, I realized that all these concepts in this sophisticated political vocabulary can be understood much more easily if they are based on respect for the individual and his or her right to choose how to live.

But what has all this to do with NATO enlargement? Every important endeavor, including the expansion of the North Atlantic alliance, needs to be based on solid moral ground. It is the moral purpose of the endeavor that draws people to it.

Today, after Sept. 11, 2001, and subsequent terrorist attacks, our mission is to extend the borders of the free world, whose shield is NATO. Countries willing and able to contribute to the strengthening of this shield were invited last week to join in maintaining it.

Now our parents can leave this world knowing that their lives had a purpose and confident in the better future of their children and grandchildren.

The writer was president of Bulgaria from 1997 to 2002. He is chairman of the Petar Stoyanov Center for Political Dialogue in Sofia and recently spent time in residence here at the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

August 2001. The President

presenting an award to US

Senator John McCain.